Views and Copies in Pandas#

In our readings on numpy, we discussed in detail how, when one subsets an array, what numpy returns is often not an entirely new array, but rather a view of the original array. These views share the underlying data of the array from which they were spawned, meaning changes to either the original array or the view have the potential to impact one another.

Since pandas Series and DataFrames are backed by numpy arrays, it will probably come as no surprise that something similar sometimes happens in pandas. As of pandas 2.0, however, I’m delighted to report the behavior of pandas is much more intuitive than numpy.

In this reading, we’ll first quickly review how views work in numpy before turning to how this behavior looks in pandas in the next reading.

A Review of Views in numpy#

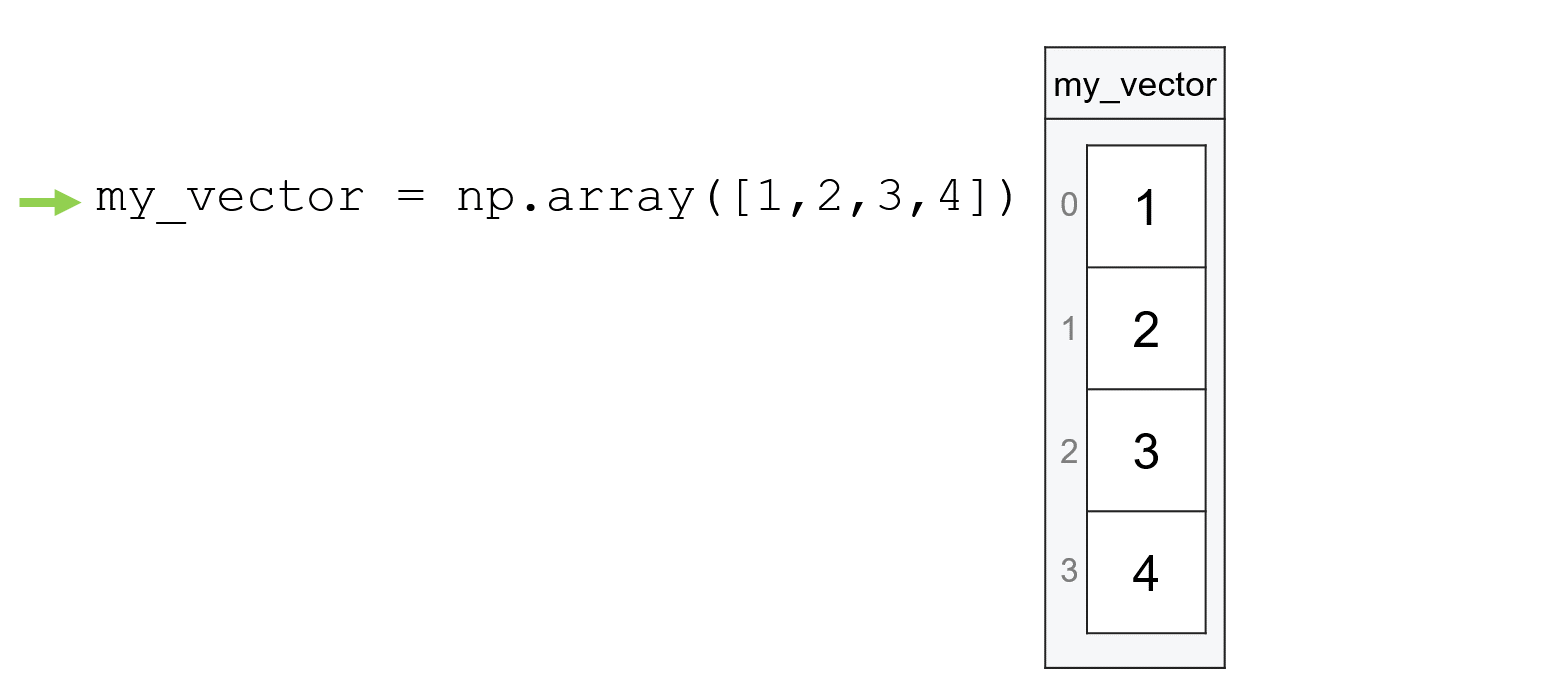

As a reminder of how views work in numpy, let’s create a simple array, subset it with slicing, and then diagram what’s going on.

import numpy as np

my_vector = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4])

my_vector

array([1, 2, 3, 4])

my_subset = my_vector[1:3]

my_subset

array([2, 3])

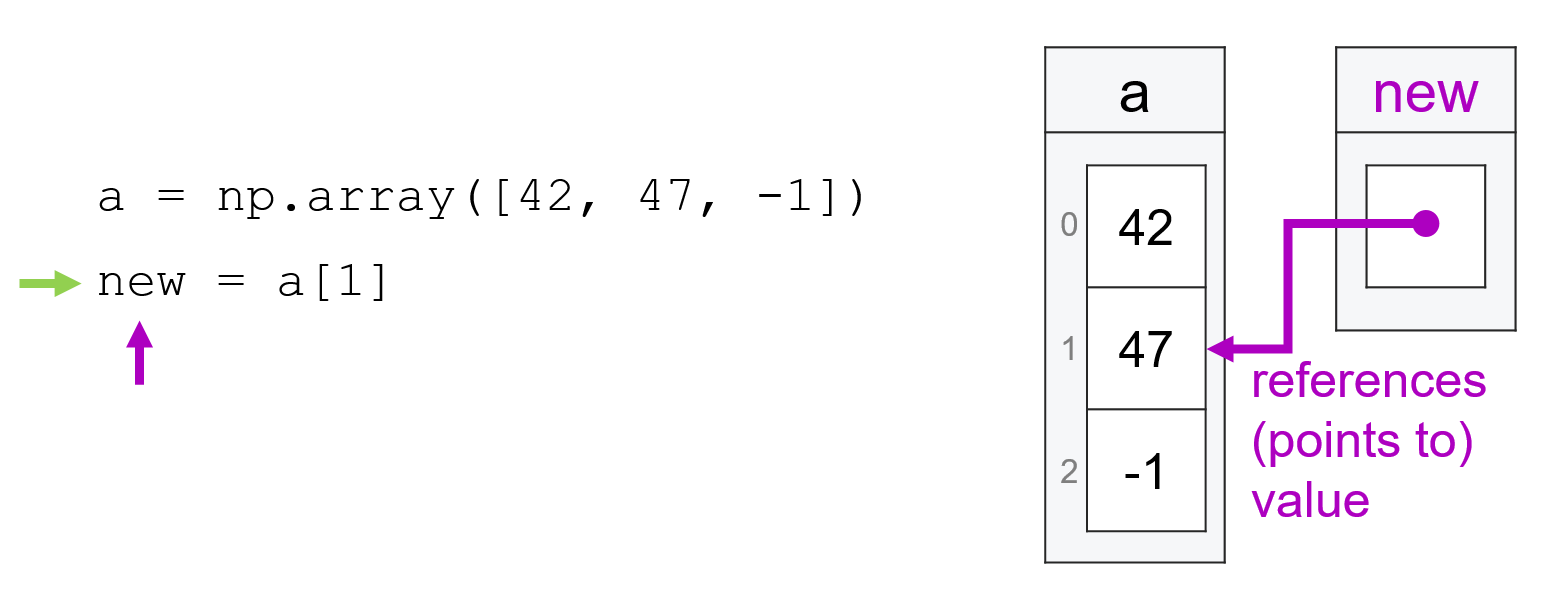

Now while it may appear that my_subset is just a new array holding the values 2 and 3, that’s actually not quite what’s going on behind the scenes. Rather, what numpy has done is create a reference to the selected subset of my_vector. We call this type of reference a view, and we can visualize what’s going on like this:

This reference is called a view because it’s not a copy of the data in the original array, but an easy way to referring back to the original array – it provides a view onto a subset of the original array.

Why is this distinction important? It’s important because it means that both variables – a and new are actually both referencing the same data, and so changes make through one variable will propagate to the other.

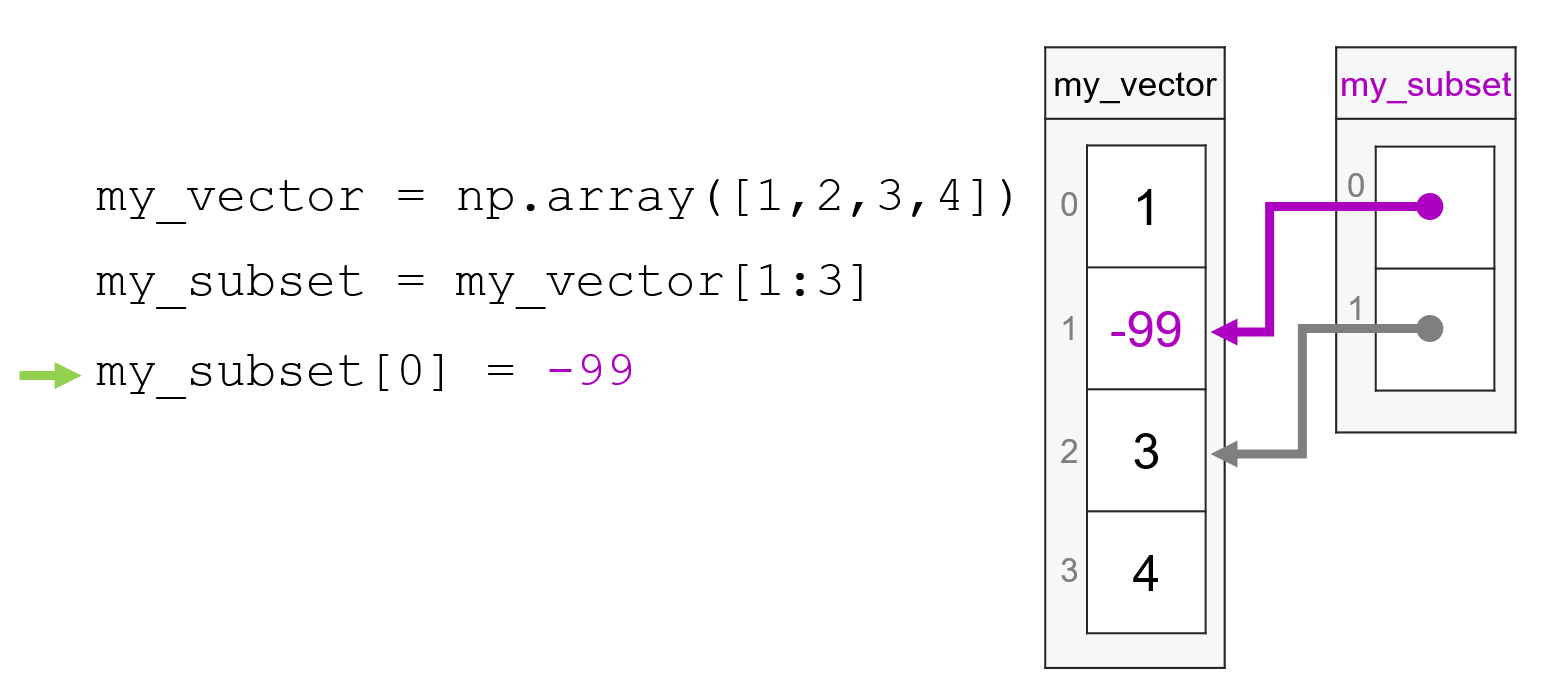

TO illustrate, suppose we change the first entry of my_subset to be -99:

my_subset[0] = -99

Since the first entry in my_subset is just a reference to the second entry in my_vector, the change I made to my_subset will also propagate to my_vector:

my_vector

array([ 1, -99, 3, 4])

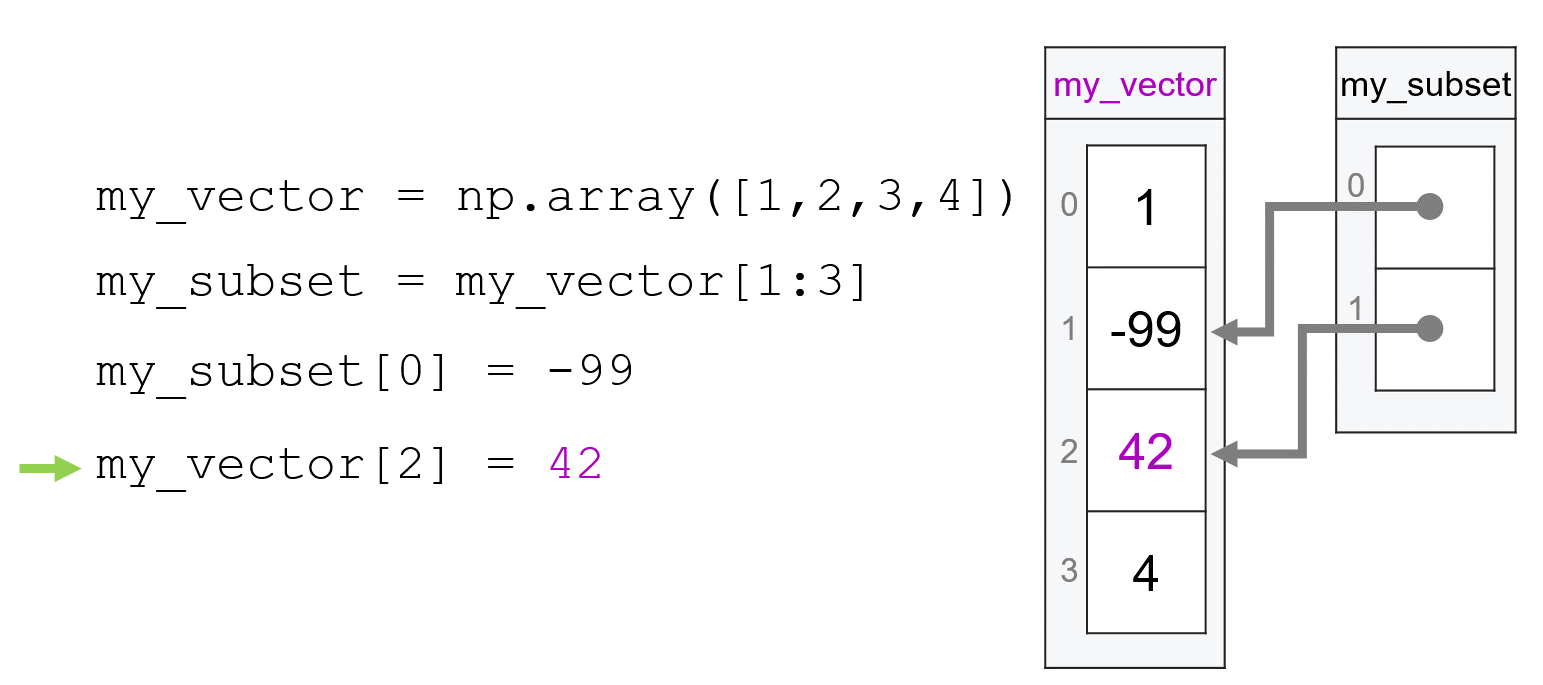

And just as edits to my_subset will propagate to my_vector, so too will edits to my_vector propagate forward to my_subset:

my_vector[2] = 42

my_subset

array([-99, 42])

Language and Symmetry#

It’s worth pausing for a moment to point out a bit of a problem with the language of views and copies. It is common, in numpy circles, to look at the example above and talk about my_vector being the original data, and my_subset as a view. And it is true that, because my_vector came first, there is a difference between my_vector and my_subset in terms of how numpy is creating and managing these objects.

But from your perspective as a user, it is important to recognize that there is a symmetric dependency between my_vector and my_subset in the example above. Yes, one may be “the original,” but once a view has been created, changes to either array have the potential to propagate to the other: changes to the my_subset may resultant changes to my_vector, and changes to my_vector can impact the my_subset (if they impact the portion of the array referenced by the subset).

So when you think about views, always remember that what we’re talking about is multiple objects sharing the same data, even if we tend to only talk about one of our arrays as “a view.”

A Reminder on When numpy Returns Views#

While a full discussion of the rules of when numpy returns a view and when it returns a copy is a little too complicated to fit into this review reading, just a reminder that not all numpy subsets are views. For example, if you subset an array with “fancy indexing” (e.g. passing a list of indices—my_array[[1, 2]]—instead of a range of sequential indices separated by a colon as we did above), you will always get a copy. We cover this in detail in Week 3 of Course 2 of this specialization, and you can also find a summary in the official numpy documentation here.