Collaboration#

Until now, the focus of this piece has been on individual coding practices that minimize the risk of errors. But as social science becomes increasingly collaborative, we also need to think about how to avoid errors in collaborative projects. In my experience, the way most social scientists collaborate on code (myself included, historically) is to place their code in a shared folder (like Dropbox or Box) and have co-authors work on the same files. There are a number of problems with this strategy, however:

Participants can ever be certain about the changes the other author has made. Changes may be obvious when an author adds a new file or large block of code, but if one participant makes a small change in an existing file, the other authors are unlikely to notice. If the other authors then write their code assuming the prior coding was still in place, problems can easily emerge.

There is no clear mechanism for review built into the workflow. Edits occur silently, and immediately become part of the files used in a project.

I am aware of three strategies for avoiding these types of problems:

The first and most conservative solution to this is full replication, where each team member conducts the full analysis independently and members then compare results. If results match, authors can feel confident there are no problems in their code. But this strategy requires a massive duplication of effort – offsetting many of the benefits of working on teams – and requires both authors be able to conduct the entire analysis, which is not always the case.

The second strategy is compartmentalization, in which each author is assigned responsibility for coding specific parts of the analysis. Author A, for example, may be responsible for importing, cleaning, and formatting data from an outside source while Author B is responsible for subsequent analysis. In this system, if Author B finds she need an additional variable for the analysis, she ask Author A to modify Author A’s code rather than making modifications herself. This ensures responsibility for each block of code is clearly delimited, and changes are unlikely to sneak into an Author’s code without their knowledge. In addition, authors can also then review one another’s code prior to project finalization. But there is no process for continuous review of code, and if Author A modifies a variable that later gets passed to Author B and somehow the communication about what is being passed from person to person break down… bad things can happen.

If you are interested in compartmentalization, consider defining exactly how data will be handed off in advance (what variables, what they’ll be called, unit of observation, etc.) so that the second Author in a chain can start working on their code. This can be hard when working with big, complicated tabular data, but if the data is simpler (and you can mock up a little sample of synthetic data), Author A and B can work on their code simultaneously. The more a system can be broken down into components with predefined interfaces, the easier it is to parallelize work, and the components are easier to build, understand, and test.

The final strategy is to use version control (i.e. git and github), which is by far the most robust solution and the one most used by computer scientists, but also the one that requires the most upfront investment in learning a new skill.

Version control does several things for preventing errors. First, as the name implies, it keeps track of every version of your code that has ever existed and makes it easy to go back to old versions. This service is often provided by services like Dropbox, it is much easier to review old versions and identifying differences between old and new versions in git than through a service like Dropbox, whose interface is sufficiently cumbersome and most of us never use it unless we accidentally delete an important file.

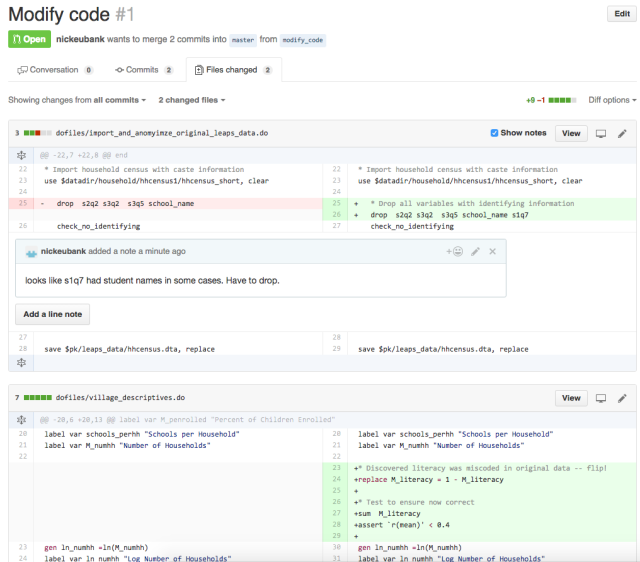

But what really makes version control exceptional is that it makes it easy to (a) keep track of what differs between any two versions, and to (b) “propose” changes to code in a way that other authors can easily review before those changes are fully integrated. If Author A wants to modify code in version control, she first creates a “branch” – a kind of working version of the project. She then makes her changes on that branch and propose the branch be re-integrated into the main code. Version control is then able to present this proposed change in a very clear way, highlighting every change that the new branch would make to the code base to ensure no changes – no matter how small – go unnoticed. The author that made the proposed changes can then ask their co-author to review the changes before they are integrated into the code base. To illustrate, Figure 1 shows an example of what a simple proposed change to code looks like on GitHub, a popular site for managing git projects online:

The Figure shows an example of a small proposed change to the code for a project on GitHub. Several aspects of the interface are worth noting. First, the interface displays all changes and the lines just above and below the changes across all documents in the project. This ensures no changes are overlooked. (Authors can click to “unfold” the code around a change if they need more context.) Second, the interface shows the prior contents of the project (on the left) and new content (on the right). In the upper pane, content has been changed, so old content is shown in red and new content in green. In the lower pane, new content has just been added, so simple grey space is shown on the left. Third, authors can easily comment (and discuss) individual lines of code, as shown here. (If you’ve somehow gotten to this page without learning git and github, just see the tutorial on that topic here!